Spotlight on Pedro Costa

I have previously mentioned my more than 3.5 year quest to track down the films of Pedro Costa. The need to discover his films only increased after reading a lot of written material about his filming methods both on the internet and in film magazines. Ofcourse, a lot of the material was generated after a retrospective of his work was shown in a few select North American cities from 2007-2008. The retrospective never made it out to my city so I had to play a waiting game before seeing something, anything, by him. Thankfully, the surfacing of a few Pedro films prevented a complete drought. In the fall of 2008 it was Casa da Lava and in 2009 it was Where Does Your Hidden Smile Lie? and O Sangue that wet my appetite. Now this year with the DVD release of the Fontainhas Trilogy, I can officially end the quest.

In addition to the Fontainhas films, I rewatched O Sangue to form a spotlight:

O Sangue (1989)

Ossos (1997)

In Vanda’s Room (2001)

Colossal Youth (2006)

Tarrafal (2007, Short film)

Rabbit Hunters (2007, Short film)

The beginning

It is hard to believe that O Sangue marked Costa's directorial debut. The film looks and feels like a work of an established master with every frame a work of art. The visuals of O Sangue are beautiful and the sound is hypnotic and dreamy. The opening moments take place in darkness and the sounds of a car stopping, a door slamming and footsteps usher the film to life. It is remarkable to see a first time director take such a bold approach to open his film. But that is Costa in a nutshell -- bold and willing to take risks.

Adrian Martin's essay included in the Second Run DVD of O Sangue is one of the best pieces of film criticism that I have ever read. Unfortunately, the full essay is not online but the following excerpt is a tasty introduction:

From the very first moments of his first feature Blood (O Sangue, 1989), Pedro Costa forces us to see something new and singular in cinema, rather than something generic and familiar. The black-and-white cinematography (by Wenders compatriot Martin Schâfer) in Blood pushes far beyond a fashionable effect of high contrast, and into something visionary: whites that burn, blacks that devour. Immediately, faces are disfigured, bodies deformed by this richly oneiric work on light, darkness, shadow and staging.

Carl Dreyer in Gertrud gave cinema something that Jacques Rivette (among others) celebrated: bodies that ‘disappear in the splice’, that live and die from shot to shot, thus pursuing a strange half-life in the interstices between reels, scenes, shots, even frames. Costa takes this poetic of light and shade, of appearance and disappearance – the poetic of Dreyer, Murnau, Tourneur – and radicalises it still further.

In Blood, there is a constant, trembling tension: when a scene ends, when a door closes, when a back is turned to camera, will the character we are looking at ever return? People disappear in the splices, a sickly father dies between scenes, transforming in an instant from speaking and (barely) breathing body to heavy corpse.

Blood is a special first feature – the first features of not-yet auteurs themselves forming a particular cinematic genre, especially in retrospect. Perhaps it was from Huillet and Straub’s Class Relations that Costa learnt the priceless lesson of screen fiction, worthy of Sam Fuller: start the piece instantly, with a gaze, a gesture, a movement, some displacement of air and energy, something dropped like a heavy stone to shatter the calm of pre-fiction equilibrium. To set the motor of the intrigue going – even if that intrigue will be so shadowy, so shrouded in questions that go to the very heart of its status as a depiction of the real. So Blood begins sharply, after the sound (under the black screen) of a car stopping, a door slamming, footsteps: a young man has his face slapped. Cut (in a stark reverse-field, down an endless road in the wilderness) to an older man, the father. Then back to the young man: “Do what you want with me.” The father picks up his suitcase (insert shot) and begins to walk off … The beginning of Colossal Youth also announces, in just this way, its immortal story: bags thrown out a window, a perfect image (reminiscent, on a Surrealist plane, of the suitcases thrown into rooms through absent windows, the sign of a ceaseless moving on and moving in, in Ruiz’s City of Pirates) of dispossession, of beings restlessly on the move from the moment they begin to exist in the image.

Michael Guillen's website is once again an essential stop about the film.

Away to Fontainhas

The origin of the Fontainhas trilogy can be traced back to Costa's filming of Casa de Lava in Cape Verde when he was asked by the locals to take their letters to relatives living in Fontainhas, on the outskirts of Lisbon. Costa took those letters to Fontainhas and the rest is cinematic history.

Ossos is the only out and out fictional Fontainhas film with In Vanda's Room and Colossal Youth blurring the line between documentary and fiction. Ossos has a beautiful rhythm to it and forms a perfect cinematic example of an arrival city. Fontainhas forms an entry point for migrants arriving from Cape Verde or other parts of Portugal. The film shows residents leaving for jobs to Lisbon early in the day and returning in the evening. Not all the residents of Fontainhas might have wanted to move to the city but by the end of In Vanda's Room all the residents are forced to relocate due to the destruction of Fontainhas.

The cinematic jump from Ossos to In Vanda's Room is beautifully explained by Cyril Neyrat:

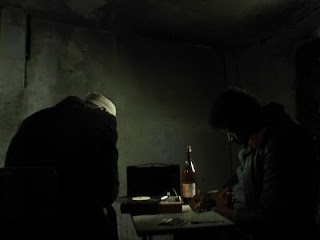

His work’s second primal scene has taken on the luster of legend, though it is undoubtedly true and absolutely practical. In 1997, Pedro Costa made Ossos in Fontainhas. This was a traditional production, shot in 35 mm, with tracks, floodlights, and assistants. Costa was a professional, a part of the Portuguese film industry. The shoot proceeded with everyone doing his job, following the routine of European art film. And the uneasiness grew, the feeling that a lie was being told, that an imbalance both moral and totally concrete was taking root on both sides of the camera. Costa later said: “The trucks weren’t getting through—the neighborhood refused this kind of cinema, it didn’t want it.” Too much squalor and despair in front of the camera, too much money, equipment, and wasted energy behind it. And too much light shining in the night of a neighborhood of manual laborers and cleaning women who got up at 5:00 a.m. So one night, Costa decided to turn off the lights and pack up the extra equipment, in an attempt to diminish the shameful sense of invasion and indecency. His action was doubly groundbreaking because in what he did, Costa found his own light, that quality of darkness and nuance he would constantly hone from that night on, and because he understood that the cinema of tracking shots, assistants, producers, and lights was not his. He didn’t want it. What he wanted was to be alone in this neighborhood with these people he loved. To take his time, to find a rhythm and working method attuned to their space and their existence. To start with a clean slate, from scratch. To reinvent his art. Three years after this leap into the void, In Vanda’s Room became the result of this departure—in Costa’s work but also in the history of the cinema.

Colossal Youth

Notes on the third film of the trilogy are reprinted as is from my 2010 Movie World Cup, Group G notes.

Colossal Youth is a living breathing painting that lets us observe its beauty and allows us to listen in to the sounds flowing within the canvas.

The mesmerizing opening shot is an indication of the beauty that lies ahead.

The film completes the Fontainhas trilogy and picks up after most of the residents from In Vanda's Room have been relocated to pristine lifeless clean apartment complexes.

Vanda is back as well, along with her cough, but this time around it is Ventura who is the camera's main focal point. Here he goes looking for Vanda.

Ventura has to select his apartment but he is taking his time and is in no hurry. The clean walls of the apartment hold no joy for Ventura as his heart is torn in between Fontainhas and his dream Lava House in Cape Verde.

Fontainhas provides Ventura an opportunity to do most of his thinking from his red throne where he can view the disappearing neighbourhood.

And there is just one scene where Costa's camera gives a glimpse of life that exists beyond the two worlds of Fontainhas and the apartment complex. This scene shows lights glittering in the distance and is the first indication of a city's existence in both Colossal Youth and In Vanda's Room.

Otherwise, Costa's camera is only focused on the relevant details, be it alleys, walls or faces.

And finally, the music and words of the infectious liberation song that Ventura plays on the record player stay long in the mind even after all the credits have taken leave.

Epilogue

The two short films Tarrafal and Rabbit Hunters continue the adventures of Ventura and provide a glimpse of life after Fontainhas.

A quote from Tarrafal:

I want to go back to Cape Verde and rest these bones.

Maybe one day Costa’s camera will return to Cape Verde and complete the cinematic circle he started with Casa de Lava.

1 comment:

Hi,

We've just published a book by portuguese film director Pedro Costa.

CASA DE LAVA - CADERNO

A scrapbook that Pedro kept during the making of Casa de Lava.

Please take a look at it here:

www.pierrevonkleist.com

Post a Comment