Marco Muller, former head of the Venice Film Festival, incurred the wrath of many people when Venice decided to hold a retrospective of Fernando Di Leo’s films:

"I was accused by a lot of Italian critics of having lost any sense of the institutions by opening the gates of the festival to trash cinema," says Venice Festival director Marco Muller.

Until recently, Muller points out, the work of filmmakers such as Di Leo was regarded with disdain in Italy. Their films were far more readily available in the UK and US than in Italy.

"Italian audiences think these are bad movies, cheap movies," acknowledges Germano Celant, artistic director of the Prada Foundation (which backed the restoration of films at the Tate.)

So Muller needed someone like Tarantino who had high praise for Fernando Di Leo:

In their battle to rehabilitate Di Leo and his colleagues, Muller and Celant had one key ally: Tarantino. The director came to Venice to introduce the movies.

"I needed Quentin. I knew he would be very loud as a spokesman for Italian B movies," Muller recalls. At the festival, Tarantino's crusading zeal and sheer force of personality helped win round older critics to the idea that the low-budget films made in their backyard in the Seventies were worth reviving. Meanwhile, younger audiences turned up in their droves, curious to see films that had had such a direct influence on Kill Bill and Pulp Fiction.

Tarantino’s words are indeed full of praise:

"One of the first films I watched was pivotal to my choice of profession. It was I Padroni della Città (Mister Scarface). I had never even heard the name Fernando Di Leo before. I just remember that after watching that film I was totally hooked," Tarantino recently recalled. "I became obsessed and started systematically watching other films directed by Di Leo. I owe so much to Fernando in terms of passion and filmmaking".

The Four film DVD box set from RARO video which was digitally restored in collaboration with the Venice Film Festival and The Prada Foundation naturally contains a quote from Tarantino on the front cover:

I am a huge fan of Italian gangster movies, I’ve seen them all and Fernando di Leo is, without a doubt, the master of this genre.

This box set also marked my first foray into the world of Fernando Di Leo.

Caliber 9 / Milano calibro 9 (1972)

The Italian Connection / La mala ordina (1972)

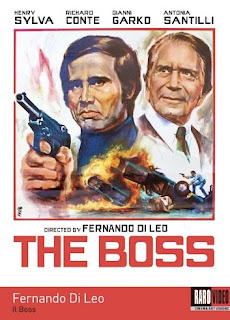

The Boss (1973)

Rulers of the City / I padroni della città (1976)

Politics, Crime and Women

The four films are B-grade works given their low budget nature, poorly synched post-dubbed dialogues, discontinuous editing and over the top acting. Still, once this initial impression is brushed off, the films have relevant political and social commentary about corruption and organization of the mafia families. The films show how government policies assisted in the dispersal of the mafia’s organizational structural from the South to the North which in turn opened the door for outside forces to get a toe in resulting in more bloodshed and power struggle. The films contain many memorable action sequences and an assortment of mafia bosses, rival groups, hitmen, pimps, cops and ample naked women.

Caliber 9 shows how a newly released criminal Ugo Piazza (Gastone Moschin) wants to get on with his normal life but neither his former colleagues or the police want to leave him alone. The criminals are convinced Ugo stole their money so they want it back while the police want him to become an informer. The film shows how the complicated internal dynamic between a criminal organization results in police being rendered powerless. Ugo is a man of few words so naturally the film features many wonderful dialogue-less moments including an impressive opening sequence which shows how a criminal operation features many participants whose role might be as simple as picking up a bag from a train.

The Italian Connection shows the link between criminal groups in New York and Italy. In order to settle a score, two American hitmen arrive in Italy to get rid of a pimp Luca Canali (Mario Adorf). However, as it transpires, Luca Canali is just a scapegoat but once the body count starts rising, it is too late turn back. The two hitmen can be clearly be seen as inspirations for Vincent Vega (John Travolta) and Jules Winnfield (Samuel L. Jackson) in Pulp Fiction.

The Boss is the most accomplished film of the pack as it outlines the closeness of familial ties in running a mafia group and shows how police, mafia and politicians are all connected in a vicious cycle of power. Loyalty is supposed to be of utmost importance but loyalty can easily be negotiated when everyone wants a slice of power. The film contains a remarkable opening sequence where Lanzetta (Henry Silva) uses a bazooka to blow up criminals in a movie theater. The opening execution results in a major cleanup of the entire criminal hierarchy and the film contains a large amount of betrayals which are planned out like chess moves.

The above three films are part of a noir trilogy with Rulers of the City being a loose addition to the group. Rulers of the City also known as Mister Scarface starts off on a light hearted flirtatious tone when a money collector Tony (Harry Baer) is prowling the streets in his fancy red Puma GT convertible and eyeing women, who naturally cannot get enough of him either. Tony is eager to move up the ranks in his criminal organization and decides to impress his bosses by conning Manzari aka Scarface (Jack Palance). Of course, cheating Scarface comes with a very high price and that starts a domino effect of score settling executions.

Inspiration & an Indian connection

The films of Fernando Di Leo may be crude B-grade films but they also contain many ingredients found in subsequent gangster/mafia films. It is easy to see how various filmmakers could have taken elements from Fernando Di Leo’s films and incorporated them in a more polished framework and produced works that would have gotten critical approval. In fact, many elements from various B-grade films can serve as inspiration for elements found in studio produced A-pictures. The following quote from Martin Scorsese in Geoffrey Macnab’s article rings true:

As Scorsese has pointed out, one of the paradoxes about B-movies is that they "are freer and more conducive to experimenting and innovating" than A-pictures.

Studio films are reluctant to take risks and often follow tried and tested formulas while B-grade films have to get the attention of a potential audience in whatever way they can. This usually means such films dispense worthy technical aspects in preference for over the top action sequences or an abundance of sex and nudity. Basically, their films need talking points to help spread the word. Also, these B-grade films are not afraid to openly criticize the state and can feature plenty of social commentary meant to win the approval of the common citizen. Watching the villains and scantily clad women in Fernando Di Leo films reminded me of the “angry man” films of Amitabh Bachchan from the 1970-80's.

A majority of these 1970-80's Bollywood films that Amitabh acted in were action flicks that featured over the top gangsters/corrupt evil men and had substandard technical aspects. However, the films had a huge following because they played on the sentiments of the oppressed working man. The common man vs corruption element is not present in Fernando Di Leo’s films as his Italian crime films focus exclusively only on elements within the criminal organization. Instead, Ram Gopal Varma’s stellar Satya (1998) and Company (2002) share traits with Fernando Di Leo’s films. Of course, there is no direct line from Fernando Di Leo to Ram Gopal Varma because Varma used real Mumbai mafia as inspirations for his films but an association between Di Leo and Varma exists solely because of how politics is embedded in the everyday life of both Italy and India.

In both countries, passionate debate about corrupt politicians is never wanting and for good reason. So it is not surprizing to find films from both countries containing corrupt criminals openly making deals with cops and politicians.