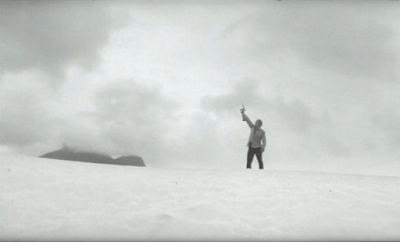

El coraje del pueblo / The Night of San Juan (1971)

Jatun Auka (1974)

I hadn’t come across any of Jorge Sanjinés’ films when exploring Bolivian cinema a decade ago. Now in 2024 when doing a similar search, his name showed up quite a bit. This change in internet searches feels driven by changing political landscape in Bolivia more than just chance or timing. Given the topic of Sanjinés films, it makes sense why it is likely easier to discuss his films openly in the last few years than it was in the early 2000s. As per this article by Carla Suárez, Jorge Sanjinés

“particularly focused on documenting indigenous cultures of the Andes: Aymara and Quechua. Sanjinés, an avid critic of colonialism, initiated his cinematic journey under the guiding principle “el cine junto al pueblo” (“cinema with the people”). He took a revolutionary Marxist approach to documentary filmmaking with the mission of giving a voice to the oppressed people of the Andean nation. In 1966, Sanjinés founded the Ukamau Group alongside screenwriter Oscar Soria, cinematographer Antonio Eguino, producer Beatriz Palacios and filmmaker Alfonso Gumucio. The group was named after the title of their first feature-length film Ukamau (meaning “and so it is” in Aymara).” Carla Suárez, 2021

I would like to speculate that the election of Evo Morales in Bolivia likely ushered a new interest in the cinema of Jorge Sanjinés and the Ukamau Group he co-founded. This is because in 2006 Bolivia finally had a president who came from the country’s indigenous population. Given the topics that Sanjinés explored in his films, it likely was easier to discuss them once the country had someone like Morales at the forefront.

In addition, Sanjinés' films especially such as Jatun Auka showcases the struggle of ordinary people against the wealthy land owners who used the strength of the military to suppress the people. This film also shows the role Americans played in training the Bolivian generals. Such cinema is labeled leftist or Marxist cinema and is rarely talked about in North American film critics sections. Somehow talking about guerrillas, resistance isn’t favoured by mainstream critical publications due to how they are funded. This also could be another reason why the cinema of Sanjinés was missing in the English language discourse I tried to search in the early 2000s.

Ukamau Group and Direct Cinema

Carla Suárez likens the cinema movement of Jorge Sanjinés to that of Neorealist cinema and cinéma direct:

"New Latin American Cinema is a film movement, inspired by Italian Neorealismo and Québec documentary genre cinéma direct, that used cinema as an instrument of social awareness and change." Carla Suárez, 2021

One of the aspects of Direct Cinema is the embedded nature of filmmaking where the filmmaker immerses themselves in the environment:

“For the cinéma direct filmmakers, the point of departure is the filmmaking process in which the filmmaker is deeply implicated as a consciousness, individual or collective. It is this process--this consciousness--which gives form and meaning to an amorphous objective reality. Instead of effacing their presence, the filmmakers affirm it.” David Clandfield’s essay From the Picturesque to the Familiar: Films of the French Unit at the NFB (1958-1964).

In this regard, Jorge Sanjinés’ two films seen as part of this spotlight meet the criteria as he clearly immerses himself in the local/village surroundings to depict events. The slight variation for The Night of San Juan is that the film is a documentary-fictional hybrid where villagers/workers re-enact events of the massacre that happened. Such a reenactment lends a reality to proceedings.

Jatun Auka shows how exploitation of people can lead to revolution which in turn leads to a cyclical nature of violence. The finale in the film shows Bolivian military aided by US troops killing revolutionaries and their bearded leader is also a reminder that it was in Bolivia that Che Guevara was killed.

Latin America has had many examples of filmmakers showcasing the human impact of revolution in their films. Patricio Guzmán is one of the best examples with his The Battle of Chile while from an overarching political exploration, Octavio Getino and Fernando E. Solanas’ The Hour of the Furnances (1968) comes to mind. The cinema of Glauber Rocha also explored such topics. Looking beyond Latin America, Indian director Shyam Benegal’s cinema also has a lineage to Direct Cinema in its depiction of plight of villagers.

References / Reading material:

Carla Suárez, Emergence of Indigenous Cinema in Bolivia: The Ethnographic Gaze of Jorge Sanjinés and the Ukamau Group.

Alonso Aguilar: Foundations of Resistance in Bolivian Cinema.

Direct Cinema covered earlier in this blog.