It is always hard to put together an end of the year list when one does not have reasonable access to films from around the world. In previous years, I was fortunate to see many worthy cinematic gems thanks to film festivals such as CIFF, VIFF and Rotterdam. Of course, depending on single screenings at film festivals as a primary source for foreign cinema is never a viable option because of the cost and effort involved in attending multiple film festivals. So when the number of film festival offerings dropped in 2011, so did my access to foreign cinema. Thankfully, the year was not a complete washout and I still managed to catch a decent number of worthwhile films. As usual, the list features older titles that I could only see this year theatrically or on DVD.

Favorites roughly in order of preference

1) Le Quattro Volte (2010, Italy co-production, Michelangelo Frammartino)

Michelangelo Frammartino’s remarkable film uses an unnamed town in Calabria as an observatory to examine the metaphysical circle of life. Depicting such metaphysical topics is not an easy task, but Frammartino pulls this off with considerable ease, plenty of humour, tender emotions and a pinch of mystery.

2) Do Dooni Chaar (2010, India, Habib Faisal)

Habib Faisal’s directorial debut astutely depicts the struggles of a middle class family in Delhi. The Duggals may be fictional characters but one can easily find reflections of their characters in virtually every Delhi colony. Filmed entirely on location, Do Dooni Chaar is absolutely charming and features two excellent performances from Rishi Kapoor and Neetu Singh. The film only got a limited release in 2010 but thankfully a DVD release in 2011 means the film can be seen by a larger audience.

3) Drive (USA, Nicolas Winding Refn)

Drive perfectly adapts James Sallis’ book while carving out a distinct identity of its own. Like Driver's car, the film is easily able to shift gears and speed up when needed and slow down in a few sequences. On top of that, the film is enhanced with a visual and musical style that evokes the cinema of Michael Mann with a pinch of David Lynch.

4) A Separation (Iran, Asghar Farhadi)

In discussing a conflict in his actuality film A Married Couple, the late Allan King remarked that viewers often projected their feelings on the screen and took sides with one of the characters. King’s words come to mind when watching the conflict in A Separation, a film that refuses to take sides with either of the characters. Some calculated editing and the distance maintained by the camera in a few scenes means that viewers are forced to believe everything they see on face value whereas in reality, the truth is hidden in between the cuts. A truly remarkable film that starts off with a divorce hearing but then moves in a much richer direction by observing humans in their moments of fear, stress and anxiety.

5) Dhobi Ghat (India, Kiran Rao)

Dhobi Ghat pays a beautiful and poetic tribute to Mumbai by exploring the emotional state of four characters. The script shrinks the vast and chaotic city down to the microscopic level of these four characters so that they can be observed in tight quarters. Each character has their own set of complex problems and Kiran Rao lets the actors brilliant expressions and body language form a guide to their inner feelings. Throughout the film, the four actors appear to be living their parts as opposed to acting out scripted lines.

6) Another Year (2010, UK, Mike Leigh)

A happily married couple serve as a sponge to absorb the misery of their friends. The film shows that some people are predisposed to always emit a negative energy while there are a few who are strong enough to withstand all the unhappiness around them.

7) Nostalgia for the Light (2010, Chile co-production, Patricio Guzmán)

Just as rays of light are delayed in their arrival to our planet, horrors of the past sometimes take a long time before they are unearthed. Patricio Guzmán’s emotional and meditative film manages to connect exploration of the stars with truths buried in the ground.

8) Aurora (2010, Romania co-production, Cristi Puiu)

Viorel’s (Cristi Puiu) disenchantment and frustration with society around him continues to build until he acts out in a burst of violence. However, the film is not concerned with the consequences of his actions but is more interested in his behavior prior to and after his violent act. Aurora is a fascinating character study that is packed with plenty of dark humor and features a remarkable climax that dives into the same rabbit hole that consumed Mr. Lazarescu (The Death of Mister Lazarescu) and Cristi (Police, Adjective).

9) The Kid With a Bike (Belgium co-production, Jean-Pierre Dardenne/Luc Dardenne)

The film’s non-stop energy is personified by the young lead character who is able to take all the kicks and roll with the punches. A truly magnificent film but then again one would not expect any less from the Dardennes.

10) Melancholia (Denmark co-production, Lars von Trier)

The end of the world sequence naturally grabs all the attention but the film’s dramatic core lies in the wedding dinner where sharp jabs are traded. These honest verbal punches echo The Celebration and Rachel Getting Married but the words in Melancholia pack more venom and are meant to break the other person down. Justine (Kirsten Dunst) desperately tries to make things work but deep down she knows that some celestial bodies are meant to collide and destroy each other.

11) The Tree of Life (USA, Terrence Malick)

A perfect symphony of camera movements and background score elevates one family’s tale into a much grander scale. The camera continuously zips around the characters, hovers over them, dives down low or swings from a corner in the room. The camera even moves back in time where it patiently captures the big bang and peers into the future as well.

12) Flowers of Evil (2010, France, David Dusa)

David Dusa’s remarkable debut feature is one of the most relevant films to have emerged in recent years. It is a rare film that depicts the revolutions of change taking place around the world by smartly incorporating social media such as facebook, twitter and youtube within the film’s framework. The film also features a groovy background score and makes great use of Shantel’s Disko Boy song.

Note: I was part of the three person jury that awarded this best film in the Mavericks category at the Calgary International Film Festival.

13) The Whisperer in the Darkness (USA, Sean Branney)

Sean Branney’s perfect adaptation of H.P Lovecraft’s short story remarkably recreates the look and feel of 1930’s cinema. The entirely black and white film uses the background score to maintain tension and suspense throughout. In fact, the tension does not let up until the 90th minute when a few moments of rest are allowed before the film heads towards a pulsating finale.

This film was also in the Mavericks Competition at CIFF.

14) Alamar (2009, Mexico, Pedro González-Rubio)

A tranquil and beautiful film about a father’s journey with his son. This is a perfect example of a film that proves that one does not need 3D to have an immersive cinematic experience.

15) Meek’s Cutoff (2010, USA, Kelly Reichardt)

The setting may be 1845 but at its core Meek’s Cutoff is a contemporary film about a journey through an unknown and potentially dangerous landscape. How much faith should be placed on a stranger? If this was such an easy question to answer, then the world would indeed have been a better place.

16) Attenberg (2010, Greece, Athina Rachel Tsangari)

A warm and tender film that puts a spin on a conventional coming-of-age tale by featuring honest communication between a father and daughter.

17) Kill List (UK, Ben Wheatley)

Ben Wheatley’s film packs quite a powerful punch and increases the tension and violence as it races along at a riveting pace. One remarkable aspect of the film is that it keeps quite a few pieces off the screen thereby allowing the audience to fill in their own version of events related to the characters background and even to origins of the cult group. It is tempting to talk about the hunchback but it is best viewers are left to encounter him on their own terms.

18) The Turin Horse (Hungary co-production, Béla Tarr/Ágnes Hranitzky)

Béla Tarr crafts his unique end of the world scenario with a few bare essentials -- an old man, obedient daughter, rebel horse, untrustworthy visitors, an angry wind, potato, bucket, well, table, chair and a window. The film features an array of reverse and sideway shots that manage to open up space in a confined house setting.

19) Buried (2010, Spain/USA/France, Rodrigo Cortés)

Buried proves that in the hands of a talented director a bare bones scenario of a man buried in a coffin can make for an engaging film.

20) The Desert of Forbidden Art (2010, Russia/USA/Uzbekistan, Tchavdar Georgiev/Amanda Pope)

The Desert of Forbidden Art is a living breathing digital work of art that gives new life to paintings that are tucked away from the world. The two directors continue the work of the documentary’s subject Igor Savitsky in showcasing art to the modern world via the medium of cinema.

Honorable Mentions, in no particular order

Undertow (2009, Peru co-production, Javier Fuentes-León)

Senna (2010, UK, Asif Kapadia)

Martha Marcy May Marlene (USA, Sean Durkin)

Of Gods and Men (2010, France, Xavier Beauvois)

We Have to Talk About Kevin (UK, Lynne Ramsay)

The Ides of March (USA, George Clooney)

Shor in the City (India, Krishna D.K, Raj Nidimoru)

Blue Valentine (2010, USA, Derek Cianfrance)

Red Riding Trilogy (2009, UK, Julian Jarrold/James Marsh/Anand Tucker)

Some other notable performances/moments

The entire cast of Margin Call are fascinating to watch although Jeremy Irons steals the show with a character that oozes evil and power.

Jimmy Shergill does a commendable job of portraying a prince who is striving to hold onto power despite having no money in Saheb Biwi Aur Gangster.

Just like in last year’s Ishqiya, Vidya Balan once again upstages her male counterparts in The Dirty Picture.

The opening moments of Hugo prove that in the hands of an auteur 3D can be a breathtaking experience rather than a loud explosive mess.

Pages

Saturday, December 31, 2011

Thursday, December 29, 2011

Four Films by Fernando Di Leo

Sometimes genre filmmakers are easily dismissed by critics and their works remain ignored until some influential film festival programmer or film director rediscovers them. In the case of Fernando Di Leo, his films were brought out of the shadows thanks to the Venice Film Festival and Quentin Tarantino. Geoffrey Macnab documents this association.

Marco Muller, former head of the Venice Film Festival, incurred the wrath of many people when Venice decided to hold a retrospective of Fernando Di Leo’s films:

"I was accused by a lot of Italian critics of having lost any sense of the institutions by opening the gates of the festival to trash cinema," says Venice Festival director Marco Muller.

Until recently, Muller points out, the work of filmmakers such as Di Leo was regarded with disdain in Italy. Their films were far more readily available in the UK and US than in Italy.

"Italian audiences think these are bad movies, cheap movies," acknowledges Germano Celant, artistic director of the Prada Foundation (which backed the restoration of films at the Tate.)

So Muller needed someone like Tarantino who had high praise for Fernando Di Leo:

In their battle to rehabilitate Di Leo and his colleagues, Muller and Celant had one key ally: Tarantino. The director came to Venice to introduce the movies.

"I needed Quentin. I knew he would be very loud as a spokesman for Italian B movies," Muller recalls. At the festival, Tarantino's crusading zeal and sheer force of personality helped win round older critics to the idea that the low-budget films made in their backyard in the Seventies were worth reviving. Meanwhile, younger audiences turned up in their droves, curious to see films that had had such a direct influence on Kill Bill and Pulp Fiction.

Tarantino’s words are indeed full of praise:

"One of the first films I watched was pivotal to my choice of profession. It was I Padroni della Città (Mister Scarface). I had never even heard the name Fernando Di Leo before. I just remember that after watching that film I was totally hooked," Tarantino recently recalled. "I became obsessed and started systematically watching other films directed by Di Leo. I owe so much to Fernando in terms of passion and filmmaking".

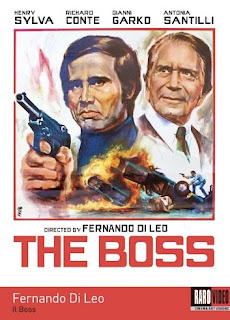

The Four film DVD box set from RARO video which was digitally restored in collaboration with the Venice Film Festival and The Prada Foundation naturally contains a quote from Tarantino on the front cover:

I am a huge fan of Italian gangster movies, I’ve seen them all and Fernando di Leo is, without a doubt, the master of this genre.

This box set also marked my first foray into the world of Fernando Di Leo.

Caliber 9 / Milano calibro 9 (1972)

The Italian Connection / La mala ordina (1972)

The Boss (1973)

Rulers of the City / I padroni della città (1976)

Politics, Crime and Women

The four films are B-grade works given their low budget nature, poorly synched post-dubbed dialogues, discontinuous editing and over the top acting. Still, once this initial impression is brushed off, the films have relevant political and social commentary about corruption and organization of the mafia families. The films show how government policies assisted in the dispersal of the mafia’s organizational structural from the South to the North which in turn opened the door for outside forces to get a toe in resulting in more bloodshed and power struggle. The films contain many memorable action sequences and an assortment of mafia bosses, rival groups, hitmen, pimps, cops and ample naked women.

Caliber 9 shows how a newly released criminal Ugo Piazza (Gastone Moschin) wants to get on with his normal life but neither his former colleagues or the police want to leave him alone. The criminals are convinced Ugo stole their money so they want it back while the police want him to become an informer. The film shows how the complicated internal dynamic between a criminal organization results in police being rendered powerless. Ugo is a man of few words so naturally the film features many wonderful dialogue-less moments including an impressive opening sequence which shows how a criminal operation features many participants whose role might be as simple as picking up a bag from a train.

The Italian Connection shows the link between criminal groups in New York and Italy. In order to settle a score, two American hitmen arrive in Italy to get rid of a pimp Luca Canali (Mario Adorf). However, as it transpires, Luca Canali is just a scapegoat but once the body count starts rising, it is too late turn back. The two hitmen can be clearly be seen as inspirations for Vincent Vega (John Travolta) and Jules Winnfield (Samuel L. Jackson) in Pulp Fiction.

The Boss is the most accomplished film of the pack as it outlines the closeness of familial ties in running a mafia group and shows how police, mafia and politicians are all connected in a vicious cycle of power. Loyalty is supposed to be of utmost importance but loyalty can easily be negotiated when everyone wants a slice of power. The film contains a remarkable opening sequence where Lanzetta (Henry Silva) uses a bazooka to blow up criminals in a movie theater. The opening execution results in a major cleanup of the entire criminal hierarchy and the film contains a large amount of betrayals which are planned out like chess moves.

The above three films are part of a noir trilogy with Rulers of the City being a loose addition to the group. Rulers of the City also known as Mister Scarface starts off on a light hearted flirtatious tone when a money collector Tony (Harry Baer) is prowling the streets in his fancy red Puma GT convertible and eyeing women, who naturally cannot get enough of him either. Tony is eager to move up the ranks in his criminal organization and decides to impress his bosses by conning Manzari aka Scarface (Jack Palance). Of course, cheating Scarface comes with a very high price and that starts a domino effect of score settling executions.

Inspiration & an Indian connection

The films of Fernando Di Leo may be crude B-grade films but they also contain many ingredients found in subsequent gangster/mafia films. It is easy to see how various filmmakers could have taken elements from Fernando Di Leo’s films and incorporated them in a more polished framework and produced works that would have gotten critical approval. In fact, many elements from various B-grade films can serve as inspiration for elements found in studio produced A-pictures. The following quote from Martin Scorsese in Geoffrey Macnab’s article rings true:

As Scorsese has pointed out, one of the paradoxes about B-movies is that they "are freer and more conducive to experimenting and innovating" than A-pictures.

Studio films are reluctant to take risks and often follow tried and tested formulas while B-grade films have to get the attention of a potential audience in whatever way they can. This usually means such films dispense worthy technical aspects in preference for over the top action sequences or an abundance of sex and nudity. Basically, their films need talking points to help spread the word. Also, these B-grade films are not afraid to openly criticize the state and can feature plenty of social commentary meant to win the approval of the common citizen. Watching the villains and scantily clad women in Fernando Di Leo films reminded me of the “angry man” films of Amitabh Bachchan from the 1970-80's.

A majority of these 1970-80's Bollywood films that Amitabh acted in were action flicks that featured over the top gangsters/corrupt evil men and had substandard technical aspects. However, the films had a huge following because they played on the sentiments of the oppressed working man. The common man vs corruption element is not present in Fernando Di Leo’s films as his Italian crime films focus exclusively only on elements within the criminal organization. Instead, Ram Gopal Varma’s stellar Satya (1998) and Company (2002) share traits with Fernando Di Leo’s films. Of course, there is no direct line from Fernando Di Leo to Ram Gopal Varma because Varma used real Mumbai mafia as inspirations for his films but an association between Di Leo and Varma exists solely because of how politics is embedded in the everyday life of both Italy and India.

In both countries, passionate debate about corrupt politicians is never wanting and for good reason. So it is not surprizing to find films from both countries containing corrupt criminals openly making deals with cops and politicians.

Marco Muller, former head of the Venice Film Festival, incurred the wrath of many people when Venice decided to hold a retrospective of Fernando Di Leo’s films:

"I was accused by a lot of Italian critics of having lost any sense of the institutions by opening the gates of the festival to trash cinema," says Venice Festival director Marco Muller.

Until recently, Muller points out, the work of filmmakers such as Di Leo was regarded with disdain in Italy. Their films were far more readily available in the UK and US than in Italy.

"Italian audiences think these are bad movies, cheap movies," acknowledges Germano Celant, artistic director of the Prada Foundation (which backed the restoration of films at the Tate.)

So Muller needed someone like Tarantino who had high praise for Fernando Di Leo:

In their battle to rehabilitate Di Leo and his colleagues, Muller and Celant had one key ally: Tarantino. The director came to Venice to introduce the movies.

"I needed Quentin. I knew he would be very loud as a spokesman for Italian B movies," Muller recalls. At the festival, Tarantino's crusading zeal and sheer force of personality helped win round older critics to the idea that the low-budget films made in their backyard in the Seventies were worth reviving. Meanwhile, younger audiences turned up in their droves, curious to see films that had had such a direct influence on Kill Bill and Pulp Fiction.

Tarantino’s words are indeed full of praise:

"One of the first films I watched was pivotal to my choice of profession. It was I Padroni della Città (Mister Scarface). I had never even heard the name Fernando Di Leo before. I just remember that after watching that film I was totally hooked," Tarantino recently recalled. "I became obsessed and started systematically watching other films directed by Di Leo. I owe so much to Fernando in terms of passion and filmmaking".

The Four film DVD box set from RARO video which was digitally restored in collaboration with the Venice Film Festival and The Prada Foundation naturally contains a quote from Tarantino on the front cover:

I am a huge fan of Italian gangster movies, I’ve seen them all and Fernando di Leo is, without a doubt, the master of this genre.

This box set also marked my first foray into the world of Fernando Di Leo.

Caliber 9 / Milano calibro 9 (1972)

The Italian Connection / La mala ordina (1972)

The Boss (1973)

Rulers of the City / I padroni della città (1976)

Politics, Crime and Women

The four films are B-grade works given their low budget nature, poorly synched post-dubbed dialogues, discontinuous editing and over the top acting. Still, once this initial impression is brushed off, the films have relevant political and social commentary about corruption and organization of the mafia families. The films show how government policies assisted in the dispersal of the mafia’s organizational structural from the South to the North which in turn opened the door for outside forces to get a toe in resulting in more bloodshed and power struggle. The films contain many memorable action sequences and an assortment of mafia bosses, rival groups, hitmen, pimps, cops and ample naked women.

Caliber 9 shows how a newly released criminal Ugo Piazza (Gastone Moschin) wants to get on with his normal life but neither his former colleagues or the police want to leave him alone. The criminals are convinced Ugo stole their money so they want it back while the police want him to become an informer. The film shows how the complicated internal dynamic between a criminal organization results in police being rendered powerless. Ugo is a man of few words so naturally the film features many wonderful dialogue-less moments including an impressive opening sequence which shows how a criminal operation features many participants whose role might be as simple as picking up a bag from a train.

The Italian Connection shows the link between criminal groups in New York and Italy. In order to settle a score, two American hitmen arrive in Italy to get rid of a pimp Luca Canali (Mario Adorf). However, as it transpires, Luca Canali is just a scapegoat but once the body count starts rising, it is too late turn back. The two hitmen can be clearly be seen as inspirations for Vincent Vega (John Travolta) and Jules Winnfield (Samuel L. Jackson) in Pulp Fiction.

The Boss is the most accomplished film of the pack as it outlines the closeness of familial ties in running a mafia group and shows how police, mafia and politicians are all connected in a vicious cycle of power. Loyalty is supposed to be of utmost importance but loyalty can easily be negotiated when everyone wants a slice of power. The film contains a remarkable opening sequence where Lanzetta (Henry Silva) uses a bazooka to blow up criminals in a movie theater. The opening execution results in a major cleanup of the entire criminal hierarchy and the film contains a large amount of betrayals which are planned out like chess moves.

The above three films are part of a noir trilogy with Rulers of the City being a loose addition to the group. Rulers of the City also known as Mister Scarface starts off on a light hearted flirtatious tone when a money collector Tony (Harry Baer) is prowling the streets in his fancy red Puma GT convertible and eyeing women, who naturally cannot get enough of him either. Tony is eager to move up the ranks in his criminal organization and decides to impress his bosses by conning Manzari aka Scarface (Jack Palance). Of course, cheating Scarface comes with a very high price and that starts a domino effect of score settling executions.

Inspiration & an Indian connection

The films of Fernando Di Leo may be crude B-grade films but they also contain many ingredients found in subsequent gangster/mafia films. It is easy to see how various filmmakers could have taken elements from Fernando Di Leo’s films and incorporated them in a more polished framework and produced works that would have gotten critical approval. In fact, many elements from various B-grade films can serve as inspiration for elements found in studio produced A-pictures. The following quote from Martin Scorsese in Geoffrey Macnab’s article rings true:

As Scorsese has pointed out, one of the paradoxes about B-movies is that they "are freer and more conducive to experimenting and innovating" than A-pictures.

Studio films are reluctant to take risks and often follow tried and tested formulas while B-grade films have to get the attention of a potential audience in whatever way they can. This usually means such films dispense worthy technical aspects in preference for over the top action sequences or an abundance of sex and nudity. Basically, their films need talking points to help spread the word. Also, these B-grade films are not afraid to openly criticize the state and can feature plenty of social commentary meant to win the approval of the common citizen. Watching the villains and scantily clad women in Fernando Di Leo films reminded me of the “angry man” films of Amitabh Bachchan from the 1970-80's.

A majority of these 1970-80's Bollywood films that Amitabh acted in were action flicks that featured over the top gangsters/corrupt evil men and had substandard technical aspects. However, the films had a huge following because they played on the sentiments of the oppressed working man. The common man vs corruption element is not present in Fernando Di Leo’s films as his Italian crime films focus exclusively only on elements within the criminal organization. Instead, Ram Gopal Varma’s stellar Satya (1998) and Company (2002) share traits with Fernando Di Leo’s films. Of course, there is no direct line from Fernando Di Leo to Ram Gopal Varma because Varma used real Mumbai mafia as inspirations for his films but an association between Di Leo and Varma exists solely because of how politics is embedded in the everyday life of both Italy and India.

In both countries, passionate debate about corrupt politicians is never wanting and for good reason. So it is not surprizing to find films from both countries containing corrupt criminals openly making deals with cops and politicians.

Monday, December 26, 2011

We have to talk about Franklin, the hunting teacher

We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011, UK/USA, Lynne Ramsay)

Early in We Need to Talk About Kevin we see a helpless Eva (Tilda Swinton) trying to calm her baby down. The baby, Kevin, keeps crying and despite Eva’s best efforts refuses to settle down.

Eva is exhausted and worn out by the time her husband Franklin (John C. Reilly) returns home in the evening. Franklin does not understand or believe about Eva’s struggles with Kevin because Franklin only sees a quiet and content baby. Franklin goes on to lovingly cradle the baby and play with the child.

Such a scene is not fiction and takes place in virtually every household where there is one stay at home parent and one working parent. The stay at home parent spends an entire day looking after the baby with no time for playing and is exhausted by the time evening rolls around. So when the working parent returns home in the evening, they usually find a calm baby and freely go about playing with the child. As a result, the working parent is often the fun parent while the stay at home parent is the workhorse looking after every need of the baby. In most cases, the stay at home parent is the mother while the father gets to be the cool parent. In a sense, such roles have existed for centuries dating all the way back to prehistoric times. During the stone ages, cavemen were the hunters who spent all their time looking for prey while the women stayed in the cave taking care of the children and cooking the food. We Need to Talk About Kevin examines the continuation of these roles in modern times and highlights the similarity by depicting archery as Franklin’s main bonding activity with his son. Franklin is passing down the ancient art of hunting to his son so it really should not be a surprize when Kevin uses this training to go hunting for live prey.

Raising a child is a difficult task and that task is much more difficult if only one parent is left to do everything. Franklin is an absent parent and he is not shown to contribute in any raising of Kevin. He tries his best to be Kevin’s friend and leaves all the disciplining to Eva which is clearly a mistake as Eva cannot handle the child on her own. When Eva loses her temper and manages to break young Kevin’s arm, she alienates Kevin who grows up to resent her. Kevin’s hatred extends beyond his mother to his young sister who also gets mistreated by Kevin. Franklin never clues in and fails to ponder over any questionable actions. When Kevin orders a box of padlocks, Franklin believes Kevin’s statement that he intends to sell the locks to make a profit. Franklin even pats his son on the back and likens him to a young “Donald Trump”. However, Kevin’s words seem dubious as he has never exhibited any entrepreneurial ambition but Franklin would be the last person to notice that.

Kevin lives in a family where he is free to do whatever he pleases because neither parent comes in his way. Both Eva and Franklin have a hands off approach towards Kevin for different reasons. Eva cannot muster up the courage to say anything to Kevin because she is tired of getting insulted by him. Also any attempt by Eva to be friendly towards Kevin backfires as Kevin is never in any mood to spend “quality time” with his mother. So Eva keeps her distance and comforts herself with a bottle of wine. On the other hand, Franklin thinks he is Kevin’s buddy and tries to play it cool. But even Franklin is not spared as his friendly behavior leads him getting stabbed in the back. Eva and Franklin are not shown to be bad parents but instead they come off as parents who cannot cope with their child and as a result neglect him. Not all neglected children grow up and turn violent like Kevin but when parents neglect their child, they leave the door open for outside forces to influence and shape their child. The film does not show any of these outside influences and as rightly observed by Srikanth Srinivasan, the film is from the perspective of Eva, which means we never get to see the full picture of how Kevin is influenced. The film’s title and layers of symbolism in each frame highlights the guilt that Eva feels with regards to Kevin’s violent act. The repeated images of blood seen throughout the film clearly indicate that Eva feels responsible for the bloodshed. As a result, Eva sees blood on her house, car, face and hair. The strange looks the neighbours give Eva when she is sanding her house indicate that the neighbours don’t see the blood but only she does.

Interestingly, the film starts off with a scene where the color red represents freedom for Eva. A series of scenes from the Spanish festival of tomatina portray that red once symbolized a time when Eva had no worries or responsibilities.

However, that same red color ends up being a burden for Eva because it represents her guilt for Kevin’s act. Naturally, the images of blood are only wiped clean after Eva has found resolution and stopped blaming herself.

We Need to Talk About Kevin saves itself from heading down a slippery slope by not including any outside influences that helped shape Kevin’s motives. When Eva presses him for an answer about his violent act, Kevin replies "I used to think I knew. Now I'm not so sure." Usually, there is no quick answer that can suffice but instead the answer lies in years of neglect, anger and resentment that comes to a boil in a single moment. The film gives snippets of these resentful moments from Kevin’s childhood into his teenage years but only from Eva’s memories. Even if the film tried to incorporate Franklin into the perspective, it is hard to think any worthwhile memories would be generated from his vantage point. Franklin unknowingly supervised Kevin’s killer training yet Franklin is blood free for all but one scene. More importantly, Franklin fails to be there for Eva. Franklin never believes Eva when she tells him about Kevin’s negative actions nor does he observe his son’s rude behavior towards his mother or sister. As a result, Eva can never approach Franklin to get him to discipline Kevin. There is clearly a problem in Franklin and Eva’s marriage but since we never learn anything about Franklin, we can only assume he is not interested in any responsibility whatsoever. In the end, Eva is left to run the household and is forced to pick up the pieces after all the arrows have been fired. One day, perhaps we can talk about Franklin and what was so important that he completely ignored his family.

Note: the casting of Jasper Newell and Ezra Miller as the younger and older Kevin is certainly a great decision as both reflect each other nicely. On top of that, both nail their role perfectly and the older Kevin oozes hatred and evil when needed.

Early in We Need to Talk About Kevin we see a helpless Eva (Tilda Swinton) trying to calm her baby down. The baby, Kevin, keeps crying and despite Eva’s best efforts refuses to settle down.

Eva is exhausted and worn out by the time her husband Franklin (John C. Reilly) returns home in the evening. Franklin does not understand or believe about Eva’s struggles with Kevin because Franklin only sees a quiet and content baby. Franklin goes on to lovingly cradle the baby and play with the child.

Such a scene is not fiction and takes place in virtually every household where there is one stay at home parent and one working parent. The stay at home parent spends an entire day looking after the baby with no time for playing and is exhausted by the time evening rolls around. So when the working parent returns home in the evening, they usually find a calm baby and freely go about playing with the child. As a result, the working parent is often the fun parent while the stay at home parent is the workhorse looking after every need of the baby. In most cases, the stay at home parent is the mother while the father gets to be the cool parent. In a sense, such roles have existed for centuries dating all the way back to prehistoric times. During the stone ages, cavemen were the hunters who spent all their time looking for prey while the women stayed in the cave taking care of the children and cooking the food. We Need to Talk About Kevin examines the continuation of these roles in modern times and highlights the similarity by depicting archery as Franklin’s main bonding activity with his son. Franklin is passing down the ancient art of hunting to his son so it really should not be a surprize when Kevin uses this training to go hunting for live prey.

Raising a child is a difficult task and that task is much more difficult if only one parent is left to do everything. Franklin is an absent parent and he is not shown to contribute in any raising of Kevin. He tries his best to be Kevin’s friend and leaves all the disciplining to Eva which is clearly a mistake as Eva cannot handle the child on her own. When Eva loses her temper and manages to break young Kevin’s arm, she alienates Kevin who grows up to resent her. Kevin’s hatred extends beyond his mother to his young sister who also gets mistreated by Kevin. Franklin never clues in and fails to ponder over any questionable actions. When Kevin orders a box of padlocks, Franklin believes Kevin’s statement that he intends to sell the locks to make a profit. Franklin even pats his son on the back and likens him to a young “Donald Trump”. However, Kevin’s words seem dubious as he has never exhibited any entrepreneurial ambition but Franklin would be the last person to notice that.

Kevin lives in a family where he is free to do whatever he pleases because neither parent comes in his way. Both Eva and Franklin have a hands off approach towards Kevin for different reasons. Eva cannot muster up the courage to say anything to Kevin because she is tired of getting insulted by him. Also any attempt by Eva to be friendly towards Kevin backfires as Kevin is never in any mood to spend “quality time” with his mother. So Eva keeps her distance and comforts herself with a bottle of wine. On the other hand, Franklin thinks he is Kevin’s buddy and tries to play it cool. But even Franklin is not spared as his friendly behavior leads him getting stabbed in the back. Eva and Franklin are not shown to be bad parents but instead they come off as parents who cannot cope with their child and as a result neglect him. Not all neglected children grow up and turn violent like Kevin but when parents neglect their child, they leave the door open for outside forces to influence and shape their child. The film does not show any of these outside influences and as rightly observed by Srikanth Srinivasan, the film is from the perspective of Eva, which means we never get to see the full picture of how Kevin is influenced. The film’s title and layers of symbolism in each frame highlights the guilt that Eva feels with regards to Kevin’s violent act. The repeated images of blood seen throughout the film clearly indicate that Eva feels responsible for the bloodshed. As a result, Eva sees blood on her house, car, face and hair. The strange looks the neighbours give Eva when she is sanding her house indicate that the neighbours don’t see the blood but only she does.

Interestingly, the film starts off with a scene where the color red represents freedom for Eva. A series of scenes from the Spanish festival of tomatina portray that red once symbolized a time when Eva had no worries or responsibilities.

However, that same red color ends up being a burden for Eva because it represents her guilt for Kevin’s act. Naturally, the images of blood are only wiped clean after Eva has found resolution and stopped blaming herself.

We Need to Talk About Kevin saves itself from heading down a slippery slope by not including any outside influences that helped shape Kevin’s motives. When Eva presses him for an answer about his violent act, Kevin replies "I used to think I knew. Now I'm not so sure." Usually, there is no quick answer that can suffice but instead the answer lies in years of neglect, anger and resentment that comes to a boil in a single moment. The film gives snippets of these resentful moments from Kevin’s childhood into his teenage years but only from Eva’s memories. Even if the film tried to incorporate Franklin into the perspective, it is hard to think any worthwhile memories would be generated from his vantage point. Franklin unknowingly supervised Kevin’s killer training yet Franklin is blood free for all but one scene. More importantly, Franklin fails to be there for Eva. Franklin never believes Eva when she tells him about Kevin’s negative actions nor does he observe his son’s rude behavior towards his mother or sister. As a result, Eva can never approach Franklin to get him to discipline Kevin. There is clearly a problem in Franklin and Eva’s marriage but since we never learn anything about Franklin, we can only assume he is not interested in any responsibility whatsoever. In the end, Eva is left to run the household and is forced to pick up the pieces after all the arrows have been fired. One day, perhaps we can talk about Franklin and what was so important that he completely ignored his family.

Note: the casting of Jasper Newell and Ezra Miller as the younger and older Kevin is certainly a great decision as both reflect each other nicely. On top of that, both nail their role perfectly and the older Kevin oozes hatred and evil when needed.

Friday, December 23, 2011

Putty Hill, The Arbor

Innovative Cinema

A character is busy doing something but suddenly the character stops what they are doing and looks towards the camera to answer questions by an unseen interviewer. Once the character has answered the questions, the camera steps back allowing the character to jump back into the fictional story that continues until the next stoppage to address the audience.

Such a unique and innovative approach in Matthew Porterfield’s Putty Hill manages to blur the line between documentary and fiction by incorporating interviews within the framework of scripted cinema.

This same technique of addressing the audience directly can also be found in Clio Barnard’s The Arbor where actors talk directly to the camera before the film continues.

However, there is a difference in the technique between Putty Hill and The Arbor. Porterfield’s film is fiction that uses mostly non-professional actors but The Arbor uses professional actors to lip-sync a true story. This technique is needed in The Arbor because this method is similar to the work of Andrea Dunbar on whose plays the film is based on. Clio Barnard describes this direct address technique in the film's DVD booklet:

Andrea’s fiction was based on what she observed around her. She reminded the audience they were watching a play by her use of direct address when The Girl in The Arbor introduced each scene.

I see the use of actors lip-synching as performing the same function, reminding the audience they are watching the retelling of a true story.

My work is concerned with the relationship between fiction film language and documentary. I often dislocate sound and image by constructing fictional images around verbatim audio. In this sense, my working methods have some similarity to the methods of verbatim theatre.

Verbatim theatre by its very nature (being performed in a theatre by actors) acknowledges that it is constructed. Housing estates and the people who live there are usually represented on film in the tradition of Social Realism, a working method that aims to deny construct, aiming for naturalistic performances, an invisible crew and camera, adopting the aesthetic of Direct Cinema (a documentary movement) as a short hand for authenticity. I wanted to confront expectations about how a particular group of people are represented by subverting the form.

I used the technique in which actors lip-sync to the voices of interviewees to draw attention to the fact that documentary narratives are as constructed as fictional ones. I want the audience to think about the fact that the film has been shaped and edited by the filmmakers.....

This verbatim theatre and direct audience technique results in a rich work that is a fascinating blend of improv theatre, scripted cinema and a documentary. Often, examples of all three methods take place in just one sequence.

For example, an actor describes the context of the scene the audience are about to observe.

The actor then jumps into character in a theatrical set constructed in the middle of the exact same living space the story is based on. So reality feeds into fiction which in turn reflects reality.

This direct address technique also gives the appearance of interactive cinema. In both Putty Hill and The Arbor, the camera pans across the screen before slowly stopping on a character who then addresses the audience. On first glance, this looks to have the same level of control as when a user clicks on an object of interest when scrolling across a user interface. However, this level of control is a bit misleading since it is not a two-way interaction because the audience does not have full control to listen from any character. Instead, the characters that speak up do so as per the film director’s discretion. The directors carefully adjust the audience attention on a particular character via the camera movement (pan combined with a slow focus) thereby arousing curiosity in the mind of viewers. As a result, when a character speaks up, it is not unexpected nor intrusive. In fact, the character’s words are welcome because it allows viewers to learn a bit more about events in the story.

The following example from The Arbor shows how such a one-way interactive moment takes place. This scene shows characters engaged in a heated debate which threatens to get out of hand.

A policeman leads one of the characters away.

The camera tracks the two characters and settles in on a face in the crowd

who then gives the addresses the audience directly.

Both films share a direct address technique although The Arbor has roots in Verbatim theatre while Putty Hill is a fluid blend of documentary with fiction. The two films are innovative works that break free from the conventional cinematic mould and are essential viewing.

A character is busy doing something but suddenly the character stops what they are doing and looks towards the camera to answer questions by an unseen interviewer. Once the character has answered the questions, the camera steps back allowing the character to jump back into the fictional story that continues until the next stoppage to address the audience.

Such a unique and innovative approach in Matthew Porterfield’s Putty Hill manages to blur the line between documentary and fiction by incorporating interviews within the framework of scripted cinema.

This same technique of addressing the audience directly can also be found in Clio Barnard’s The Arbor where actors talk directly to the camera before the film continues.

However, there is a difference in the technique between Putty Hill and The Arbor. Porterfield’s film is fiction that uses mostly non-professional actors but The Arbor uses professional actors to lip-sync a true story. This technique is needed in The Arbor because this method is similar to the work of Andrea Dunbar on whose plays the film is based on. Clio Barnard describes this direct address technique in the film's DVD booklet:

Andrea’s fiction was based on what she observed around her. She reminded the audience they were watching a play by her use of direct address when The Girl in The Arbor introduced each scene.

I see the use of actors lip-synching as performing the same function, reminding the audience they are watching the retelling of a true story.

My work is concerned with the relationship between fiction film language and documentary. I often dislocate sound and image by constructing fictional images around verbatim audio. In this sense, my working methods have some similarity to the methods of verbatim theatre.

Verbatim theatre by its very nature (being performed in a theatre by actors) acknowledges that it is constructed. Housing estates and the people who live there are usually represented on film in the tradition of Social Realism, a working method that aims to deny construct, aiming for naturalistic performances, an invisible crew and camera, adopting the aesthetic of Direct Cinema (a documentary movement) as a short hand for authenticity. I wanted to confront expectations about how a particular group of people are represented by subverting the form.

I used the technique in which actors lip-sync to the voices of interviewees to draw attention to the fact that documentary narratives are as constructed as fictional ones. I want the audience to think about the fact that the film has been shaped and edited by the filmmakers.....

This verbatim theatre and direct audience technique results in a rich work that is a fascinating blend of improv theatre, scripted cinema and a documentary. Often, examples of all three methods take place in just one sequence.

For example, an actor describes the context of the scene the audience are about to observe.

The actor then jumps into character in a theatrical set constructed in the middle of the exact same living space the story is based on. So reality feeds into fiction which in turn reflects reality.

This direct address technique also gives the appearance of interactive cinema. In both Putty Hill and The Arbor, the camera pans across the screen before slowly stopping on a character who then addresses the audience. On first glance, this looks to have the same level of control as when a user clicks on an object of interest when scrolling across a user interface. However, this level of control is a bit misleading since it is not a two-way interaction because the audience does not have full control to listen from any character. Instead, the characters that speak up do so as per the film director’s discretion. The directors carefully adjust the audience attention on a particular character via the camera movement (pan combined with a slow focus) thereby arousing curiosity in the mind of viewers. As a result, when a character speaks up, it is not unexpected nor intrusive. In fact, the character’s words are welcome because it allows viewers to learn a bit more about events in the story.

The following example from The Arbor shows how such a one-way interactive moment takes place. This scene shows characters engaged in a heated debate which threatens to get out of hand.

A policeman leads one of the characters away.

The camera tracks the two characters and settles in on a face in the crowd

who then gives the addresses the audience directly.

Both films share a direct address technique although The Arbor has roots in Verbatim theatre while Putty Hill is a fluid blend of documentary with fiction. The two films are innovative works that break free from the conventional cinematic mould and are essential viewing.

Saturday, December 17, 2011

Three Films by Mohamed Al-Daradji

The following three films from Iraqi director Mohamed Al-Daradji all take place in 2003, the pivotal year in which Iraq's history changed drastically.

Ahlaam (2006)

War, Love, God & Madness (2008)

Son of Babylon (2009)

Ahlaam (2006)

War, Love, God & Madness (2008)

Son of Babylon (2009)

The core of Ahlaam takes place after the American invasion but the film goes as far back as 1998 when Iraq was bogged down by sanctions. Back in 1998, the title character of Ahlaam (Aseel Adel) was on the verge of marriage while Hasan (Kaheel Khalid) was having doubts about staying in the army because he didn’t believe in serving Saddam. Mehdi (Mohamed Hashim) was troubled because his father’s past would stand in the way of him going for higher studies. These characters lives was clearly not great to begin with but their plight gets worse as the film moves along. Ahlaam’s marriage is ruined because her fiancée is taken away by the Iraqi police. She is pushed to the ground which subsequently damages her mind, eventually landing her in a mental hospital. The lack of order after the invasion causes the looters to move into that mental hospital forcing all the patients, including Ahlaam, out on the unsafe streets of Baghdad. As the film shows, most people suffered from poverty while living under the oppressive regime of Saddam. However, things got subsequently worse after the bombs started to fall in 2003 as the locals had to deal with extra problems such as looting, lack of electricity and water. The chaos and looting that spread like wildfire in 2003 causes the lives of the main characters in Ahlaam to spin further out of control. Ahlaam's fate is unresolved at the film’s end, but it is clear that it can’t be hopeful.

The documentary War, Love, God & Madness depicts the struggles and challenges in the making of Ahlaam. In 2003, Mohamed Al-Daradji and his crew entered Iraq posing as journalists (Al-Jazeera being the magic word) otherwise they feared their camera would be taken away. Once in Baghdad, Al-Daradji tried to find the only working film camera while recruiting local actors. He found it quite challenging to select a female lead especially since prospective leads backed out when they learned about the rape scene in Ahlaam. Things are further complicated when one of the crew members walked off suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Additionally, the lack of electricity and safety complicated the daily shoot schedule. Al-Daradji was on the verge of giving up and leaving Iraq but he ignored the advice of others around him and stayed to produce a sharp end product in Ahlaam despite all the stress and complications.

Son of Babylon is set a few weeks after the invasion of 2003 and starts off far away from the Iraqi capital. An older woman Um Ibrahim (Shazada Hussein) goes in search of her missing son when she learns that certain prisoners of war have been freed in Iraq. She take her grandson Ahmed (Yasser Talib) along as her missing son is Ahmed’s father.

Son of Babylon is set a few weeks after the invasion of 2003 and starts off far away from the Iraqi capital. An older woman Um Ibrahim (Shazada Hussein) goes in search of her missing son when she learns that certain prisoners of war have been freed in Iraq. She take her grandson Ahmed (Yasser Talib) along as her missing son is Ahmed’s father.

Their road journey is not an easy one because the country is in a state of flux especially when horrific truths about the past are unearthed on a daily basis. One of the film’s most emotional sequences is when the traveling duo encounter a funeral procession of recently discovered buried bodies. There are no words spoken but Um Ibrahim’s silent expressions convey her worst fears about her son’s fate.

The film manages to showcase Iraq's vast and picturesque countryside, something hardly ever seen on screen.

Also the film depicts the challenges posed by the cultural and linguistic diversity of Iraq. Um Ibrahim is Kurdish but she cannot speak Arabic so she has to rely on her grandson for translation. People have enough problems to begin with so the language barrier only adds to their frustration and confusion. Yet, no matter what language an Iraqi speaks, they are united in their suffering. The ending of Son of Babylon is even more emotional than the one in Ahlaam but such films cannot have a happy ending, not especially when there are so many unresolved matters. The end credits in Son of Babylon lists that more than a million men, women and children have gone missing in Iraq in the last 40 years. By April 2009, more than 300 mass graves were found containing between 150,000 - 250,000 bodies. The remaining are still missing so there are countless stories waiting to be told about Iraq.

Transfer of suffering

Ahlaam and War, Love, God & Madness are about the suffering of the living. However, Son of Babylon shows that suffering does not end when someone dies. In fact, their suffering gets transferred to their living relatives. And in cases when relatives have no closure about a loved one, the next generation of family members start their lives burdened with a heavy dose of pain.

Ahlaam and War, Love, God & Madness are about the suffering of the living. However, Son of Babylon shows that suffering does not end when someone dies. In fact, their suffering gets transferred to their living relatives. And in cases when relatives have no closure about a loved one, the next generation of family members start their lives burdened with a heavy dose of pain.

Smoke and Sounds

Ahlaam is a very well made film that smartly uses a grayish/dark palette to depict the chaos after the 2003 invasion. On the other hand, Son of Babylon is bright and vibrant yet most scenes feature smoke in the background thereby depicting the constant blowing up of things.

Ahlaam is a very well made film that smartly uses a grayish/dark palette to depict the chaos after the 2003 invasion. On the other hand, Son of Babylon is bright and vibrant yet most scenes feature smoke in the background thereby depicting the constant blowing up of things.

War, Love, God & Madness captures the sound of gunfire and bombing that locals have to endure on a daily basis. The documentary also features many conversations with locals in cafes and on the streets. In this regard, the film shares a bond with Sinan Antoon’s About Baghdad. It is quite fascinating to think that both Antoon and Al-Daradji were probably in Baghdad at the same time in 2003 filming their respective documentaries. Their films do feature a bit of hope because the locals believed that being rid of Saddam would eventually lead to a more happier life. It would be interesting if someone revisited the city now and interviewed the same people again because as bleak as things appeared in 2003, we now know that the coming years brought on more uncertainty.

The documentary title War, Love, God & Madness comes from an observation by a person that changing one letter in arabic transforms the word "war" into "love" and "God". That is a fascinating observation as wars are something that take place in the absence of love yet wars also take place in the name of God or if one side has too much love of their God. And when wars take place, madness is unleashed, thereby setting one on the path towards more wars.

Voices and Stories

The documentary title War, Love, God & Madness comes from an observation by a person that changing one letter in arabic transforms the word "war" into "love" and "God". That is a fascinating observation as wars are something that take place in the absence of love yet wars also take place in the name of God or if one side has too much love of their God. And when wars take place, madness is unleashed, thereby setting one on the path towards more wars.

Voices and Stories

There are plenty of books and films about Iraq yet very few of these works give an Iraqi perspective. One of the big reasons for lack of an Iraqi voice is because most of these works are based on experiences of western journalists who were living inside the Green Zone or embedded with foreign troops so their viewpoint was always a bit restricted. When these journalists went to meet the locals, they were accompanied by a translator or a bodyguard (soldier or private) and as a result, there were always filters and barriers which prevented a true Iraqi perspective from emerging. There are some exceptions such as James Longley’s incredible Iraq in Fragments which covers different parts of Iraq and outlines realistic problems facing the country. However, most films about Iraq hardly feature any Iraqis or are even shot in the country. Therefore, Mohamed Al-Daradji’s films are a pleasant surprize because they are shot entirely on location and manage to give voice to the local Iraqi people.

Mohamed Al- Daradji’s films are not made to collect box-office receipts or to win acclaim. Instead, they are made to depict essential human stories about citizens of a country the world has largely ignored even though the country name itself is regularly featured in headlines. These films won’t change the world but atleast it is good to know that there is still some relevant cinema out there that is not manufactured to win awards.

Mohamed Al- Daradji’s films are not made to collect box-office receipts or to win acclaim. Instead, they are made to depict essential human stories about citizens of a country the world has largely ignored even though the country name itself is regularly featured in headlines. These films won’t change the world but atleast it is good to know that there is still some relevant cinema out there that is not manufactured to win awards.

Friday, December 16, 2011

The Artist

The Artist (2011, France/Belgium, Michel Hazanavicius)

Once upon a time, a megastar was effortlessly able to charm his audience. He smiled and everyone fell over backwards in awe, including producers who obliged to his every whim. A photo with him could turn a nobody into a page one headline. However, he was vain and refused to change with the times so his producer dumped him. The actor was so sure of his success that he became an indie filmmaker and bankrolled his own film. The film flopped at the box-office and when the stock market crashed, the actor went bankrupt. His fortunes were sold off at an auction and he had to pawn off his expensive suits for food and drink money. He turned into an alcoholic and was so washed up that even his shadow left him. When all hope looked lost, a loving hard tried to pull him out of the quicksand. Unfortunately, once again his pride got in the way and his fate appeared sealed.

But in the tradition of a typical Hollywood studio film, he is saved thereby ensuring a feel good happy ending that everyone loves.

Cut. Insert sound. Roll credits.

Applause.

Give film universal acclaim.

Jean Dujardin and Bérénice Bejo charmingly bring their characters to life but ultimately The Artist is a rehashed studio film sold in a different package. The silent film treatment feels like a gimmick as demonstrated by the nightmare sequence in which Dujardin’s character of George Valentin loses his voice. George is told by his producer Al (John Goodman) that talkies are the future and silent actors are on the verge of extinction. This causes George to have a nightmare in which he loses his voice but all the objects and characters around him break free of the film’s silent framework -- the objects make a loud noise while characters laugh in their own voice. This sequence draws attention to itself and makes the film appear more as a spoof of the silent film era, and not as a homage. Also, watching George and Al discussing talkies while reading intertitles appears to be joke geared towards the audience and not as a relevant scenario in the context of a silent film. It would have been more effective if The Artist was a pure silent film with no reference to talkies or if the film was about the making of silent movies where characters talked in their own voice. As it stands, The Artist comes across as a muddled effort trying to use a framework of a silent film without fully embracing the methodology of the era.

Once upon a time, a megastar was effortlessly able to charm his audience. He smiled and everyone fell over backwards in awe, including producers who obliged to his every whim. A photo with him could turn a nobody into a page one headline. However, he was vain and refused to change with the times so his producer dumped him. The actor was so sure of his success that he became an indie filmmaker and bankrolled his own film. The film flopped at the box-office and when the stock market crashed, the actor went bankrupt. His fortunes were sold off at an auction and he had to pawn off his expensive suits for food and drink money. He turned into an alcoholic and was so washed up that even his shadow left him. When all hope looked lost, a loving hard tried to pull him out of the quicksand. Unfortunately, once again his pride got in the way and his fate appeared sealed.

But in the tradition of a typical Hollywood studio film, he is saved thereby ensuring a feel good happy ending that everyone loves.

Cut. Insert sound. Roll credits.

Applause.

Give film universal acclaim.

Jean Dujardin and Bérénice Bejo charmingly bring their characters to life but ultimately The Artist is a rehashed studio film sold in a different package. The silent film treatment feels like a gimmick as demonstrated by the nightmare sequence in which Dujardin’s character of George Valentin loses his voice. George is told by his producer Al (John Goodman) that talkies are the future and silent actors are on the verge of extinction. This causes George to have a nightmare in which he loses his voice but all the objects and characters around him break free of the film’s silent framework -- the objects make a loud noise while characters laugh in their own voice. This sequence draws attention to itself and makes the film appear more as a spoof of the silent film era, and not as a homage. Also, watching George and Al discussing talkies while reading intertitles appears to be joke geared towards the audience and not as a relevant scenario in the context of a silent film. It would have been more effective if The Artist was a pure silent film with no reference to talkies or if the film was about the making of silent movies where characters talked in their own voice. As it stands, The Artist comes across as a muddled effort trying to use a framework of a silent film without fully embracing the methodology of the era.

Thursday, December 08, 2011

Drive

Drive (2011, USA, Nicolas Winding Refn)

Book by James Sallis

I drive. That’s all I do.

True to his word, Driver (Ryan Gosling) does indeed drive, both for a living and for fun as well. He is a movie stunt driver by day and rent-for-hire driver by night. His conditions to prospective clients are simple and to the point:

Tell me where we start, where we're going and where we're going afterwards, I give you five minutes when you get there. Anything happens in that five minutes and I'm yours, no matter what. Anything a minute either side of that and you're on your own. I don't sit in while you're running it down. I don't carry a gun. I drive.

Given that driving is his passion, it is not a surprize that when he wants to impress Irene (Carey Mulligan) and her son Benicio (Kaden Leos), Driver takes them on a car ride by asking a simple question:

You Wanna See Something?

And when he is not behind the wheel of his car, he works in a garage fine tuning cars so that they can glide in blissful motion.

His entire existence is defined by his car’s movement but even when he is living outside of his car, his internal machine is ticking away, slowly counting down the time before life gives him the green signal to speed off in his car.

This harmony with his internal self means that he is always at peace when he has to wait at a red light as the waiting period until the light turns green is synchronized with his heartbeats. Evidence of this is provided early on in the film when in the initial car getaway sequence, Driver is able to calmly wait at a red light while facing a police car straight on.

Driver is not only calm but a man of few words. Yet his silence emits a strength and portrays a man with no emotional ties. However, as often seen in noir films, an emotionless man often falls for the wrong woman.

In Driver’s case, the woman in question Irene is a perfect girl next door but the problem arises from her husband Standard (Oscar Isaac) who has a lot of unpaid debt to clear up.

One day Driver comes across Standard lying bloodied in the parking lot while his 4 year old son Benicio is in a state of shock. Driver decides to fix things. Since the film does not give Driver’s backstory, one can assume his need to do good is out of his love for Irene. However, James Sallis’ book perfectly outlines two examples of why Driver needs to help Irene and Benicio. The following section explains how Driver lost his father and was placed in a foster home.

Once he’d got his growth, his father had little use for him. His father had had little use for his mother for a lot longer. So Driver wasn’t surprised when one night at the dinner table she went after his old man with butcher and bread knives, one in each fist like a ninja in a red-checked apron. She had one ear off and a wide red mouth drawn in his throat before he could set his coffee cup down. Driver watched, then went on eating his sandwich: Spam and mint jelly on toast. That was about the extent of his mother’s cooking.

He’d always marvelled at the force of this docile, silent woman’s attack -- as though her entire life had gathered toward that single, sudden bolt of action. She wasn’t good for much else afterwards..... -- Chapter three, pages 10-11.

In one swift move, Driver lost both his parents, one permanently and the other to prison. That meant Driver was forced to fend for himself and his entire life was a struggle. So he does not want Benicio to suffer that same fate. When he sees Standard lying with his face beaten up, Driver has a flashback to his childhood and sees his youth reflected in Benicio. At that moment, Driver decides to put his life on the line to ensure that Benicio will not grow up in a broken home.

Another segment from the book explains how Driver’s need to dish out justice arose in his youth.

Driver’s first and last fight at the new school happened when the local bully came up to him on the schoolyard and told Driver he shouldn’t he hanging around Jews. Driver had vaguely been aware that Herb was Jewish, but he was still more vague about why anyone would want to make something of that. This bully liked to flick people’s ears with his middle finger, shooting it off his thumb. When he tried it this time, Driver met his wrist halfway with one hand, stopping it cold. With the other hand he reached across and very carefully broke the boy’s thumb. -- Chapter Thirty, page 137.

The film gives a few examples that Driver is not afraid to take anyone on. When a former robber approaches him for another job in a diner, Driver dismisses the man with the following words:

How about this - shut your mouth or I'll kick your teeth down your throat and I'll shut it for you.

Essentially, Driver’s life is shaped by his childhood experience and just like his mother’s sudden act of violence, Driver is willing to jolt into sudden action to defend what he believes is right. The following words from the book could easily apply to Driver...

...as though her entire life had gathered toward that single, sudden bolt of action...

This sudden bolt of action comes when Driver ruthlessly beats up a thug in an elevator while Irene watches in fear. That burst of violence scares Irene and distances her from him but Driver was only acting out what he saw in his youth. The same bolt of action takes place in the motel when Driver has to defend himself when he is attacked by Nino’s (Ron Perlman) men.

The Latin Touch & the Exotic Life

The film changes the identity of Irene’s character slightly from the book. In the book, she is Latin.

He’d been coming up the stairs when the door next to his opened and a woman asked, in perfect English but with the unmistakable lilt of a native Spanish speaker, if he needed any help.

Seeing her, a Latina roughly his age, hair like a raven’s wing, eyes alight, he wished to hell he did need help. But what he had in his arms was about everything he owned. -- Chapter ten, pages 43-44

The words in the book give Irene an angelic appearance and this is something which the film manages to depict by having a halo like gentle light lit over her head in a few scenes, especially the elevator kiss. This lighting in the film manages to save needless dialogues and give audience an idea about how Driver perceives Irene.

In the book, Driver has no money so he is always looking for cheap places to eat or to drink. However, his world is not all about inexpensive things because he incorporates some ethnic flavor in his life by eating at Latin restaurants or drinking Pacifico beer.

He caught a double-header of Mexican movies out on Pico, downed a couple of slow beers at a bar nearby making polite conversation with the guy on the next stool, then had dinner at the Salvadoran restaurant up the street from his current crib, rice cooked with shrimp and chicken, fat tortillas with that great bean dip they do, sliced cucumbers, radish and tomatoes. -- Chapter seven, page 28

The film manages to pay a tribute to this Latin influence in a very subtle way. In the supermarket sequence, Driver’s back is framed against a beer cooler packed with Corona. This is not simple product placement but the inclusion of Corona serves a purpose. Corona’s marketing campaign plays up the exotic element of drinking this Mexican beer. However, once the marketing campaign and lime is taken away, Corona is exposed for what it is -- a cheap tasteless commercial beer. It gives the illusion of being something that it is not. In a sense, it is a perfect drink for Driver as it would satisfy his criteria for drinking cheap beer with a Latin twist.

James Hansen gives another example of Driver’s preference for the less flashier side of LA:

...Despite these apparent dangers, the Driver’s world is understated, simple, and perhaps second rate – he waits on the end of a Clippers game, not the Lakers.

The book flushes out this side of Driver’s world completely but it is quite commendable that the film also manages to portray these aspects in a few cuts.

Without too many words

It is essential for the book to provide Driver’s childhood via flashbacks so as to provide context for his current behavior. However, the film does not need to provide flashbacks or a backstory because the expressions of the characters combined with snippets of dialogue should be enough. This is where writer Hossein Amini and director Nicolas Winding Refn deserve a lot of credit because they have managed to precisely extract enough material from the book to depict the various characters with no flashbacks and very little dialogue. The actors then manage to put the finishing touches by providing depth to their characters. Ryan Gosling is perfect in his role but even Ron Perlman, Albert Brooks and Bryan Cranston do great justice to their parts by conveying the right tone. A few lines of dialogue emits Nino’s frustration with his life and why he tries to pull off a nonsensical robbery. A single scene and line of dialogue is all one needs to understand Bernie Rose (Albert Brooks). When Driver first meets Bernie, Driver does not extend his hand to Bernie.

Driver: my hands are a little dirty

To which Bernie replies: so are mine

Those three words sum up Bernie’s shady personality perfectly.

Style Upgrade

Nicolas Winding Refn sprinkles the film with 1980’s music which evokes the cinema of Michael Mann. Also, Refn adds a pinch of David Lynch and that comes out in the sequence when Driver takes takes Irene and Benicio for a fun ride. The background music during the car ride channels David Lynch’s Lost Highway road, albeit the scene in Drive takes place in broad daylight.

Overall, Drive is perfect example of how to properly adapt a book and still give the film a unique identity with just a few modifications. Like Driver's car, the film is easily able to shift gears and speed up when needed and slow down in a few sequences. Easily one of the best films of the year!

[Update]: News emerged today that James Sallis will write a sequel to Drive called Driven....

Book by James Sallis

I drive. That’s all I do.

True to his word, Driver (Ryan Gosling) does indeed drive, both for a living and for fun as well. He is a movie stunt driver by day and rent-for-hire driver by night. His conditions to prospective clients are simple and to the point:

Tell me where we start, where we're going and where we're going afterwards, I give you five minutes when you get there. Anything happens in that five minutes and I'm yours, no matter what. Anything a minute either side of that and you're on your own. I don't sit in while you're running it down. I don't carry a gun. I drive.

Given that driving is his passion, it is not a surprize that when he wants to impress Irene (Carey Mulligan) and her son Benicio (Kaden Leos), Driver takes them on a car ride by asking a simple question:

You Wanna See Something?

And when he is not behind the wheel of his car, he works in a garage fine tuning cars so that they can glide in blissful motion.

His entire existence is defined by his car’s movement but even when he is living outside of his car, his internal machine is ticking away, slowly counting down the time before life gives him the green signal to speed off in his car.

This harmony with his internal self means that he is always at peace when he has to wait at a red light as the waiting period until the light turns green is synchronized with his heartbeats. Evidence of this is provided early on in the film when in the initial car getaway sequence, Driver is able to calmly wait at a red light while facing a police car straight on.

Driver is not only calm but a man of few words. Yet his silence emits a strength and portrays a man with no emotional ties. However, as often seen in noir films, an emotionless man often falls for the wrong woman.

In Driver’s case, the woman in question Irene is a perfect girl next door but the problem arises from her husband Standard (Oscar Isaac) who has a lot of unpaid debt to clear up.

One day Driver comes across Standard lying bloodied in the parking lot while his 4 year old son Benicio is in a state of shock. Driver decides to fix things. Since the film does not give Driver’s backstory, one can assume his need to do good is out of his love for Irene. However, James Sallis’ book perfectly outlines two examples of why Driver needs to help Irene and Benicio. The following section explains how Driver lost his father and was placed in a foster home.

Once he’d got his growth, his father had little use for him. His father had had little use for his mother for a lot longer. So Driver wasn’t surprised when one night at the dinner table she went after his old man with butcher and bread knives, one in each fist like a ninja in a red-checked apron. She had one ear off and a wide red mouth drawn in his throat before he could set his coffee cup down. Driver watched, then went on eating his sandwich: Spam and mint jelly on toast. That was about the extent of his mother’s cooking.

He’d always marvelled at the force of this docile, silent woman’s attack -- as though her entire life had gathered toward that single, sudden bolt of action. She wasn’t good for much else afterwards..... -- Chapter three, pages 10-11.

In one swift move, Driver lost both his parents, one permanently and the other to prison. That meant Driver was forced to fend for himself and his entire life was a struggle. So he does not want Benicio to suffer that same fate. When he sees Standard lying with his face beaten up, Driver has a flashback to his childhood and sees his youth reflected in Benicio. At that moment, Driver decides to put his life on the line to ensure that Benicio will not grow up in a broken home.