Note: almost all the films in this list are co-productions but I had to leave out some co-productions due to the source of main production funding. For example, Rungano Nyoni’s stunning I Am Not a Witch would have made this top 10 but it was UK’s entry to the Oscars so it couldn't be included. Jessica Beshir’s hypnotic Faya Dayi is an American-Ethiopian co-production but it appears to be ineligible for inclusion and the same goes for Abou Leila, a personal favourite. The Battle of Algiers is included in my Italian films list.

Top 10 African Films of All Time

1. Touki Bouki (1973, Senegal, Djibril Diop Mambéty)

Djibril Diop Mambéty’s landmark film Touki Bouki gives a good slice into an emerging African nation complete with street shots dripping with poverty, heated arguments at the market, youths looking for jobs and trouble, a young couple dreaming of a better future, corruption and payback lurking around the corner with a club in hand and unflinching slaughter shots. The relaxed lingering shots, mixed with carefully spliced scenes give this movie a surreal feel. In addition, plenty of symbolism in the movie with a cow's capture and slaughter being the most commonly used symbol to echo the mental and physical entrapment of the citizens. An incredible film that was ahead of its time.

2. Soleil Ô (1967, Mauritania/France, Med Hondo)

Med Hondo’s highly relevant and urgent film is an insightful look at the connection between colonialism, racism, migration and immigration. The film covers migration from Africa to France yet the topic is relevant for many other nations in Africa, Asia, South America whose citizens left (and continue to leave) for better jobs in their former colonizing country.

3. Timbuktu (2014, Mauritania/France/Qatar, Abderrahmane Sissako)

At its core, Timbuktu is about the centuries old problem of people from one nation/culture using violence/force to impose their ways onto another culture. As the film shows, violent exchanges often results in victims not getting justice and creates a perpetual circle of violent reactions to avenge the violent act. As a result, the film has an an air of inevitability around it.

Even though the film rejects any notion of a happy ending, Sissako has infused his film with plenty of dark satire which results in a few comical scenarios, yet the implications are nothing to laugh at. For example, in one scene, the militants want the local women to cover every part of their body, including wearing gloves on their hands. Yet, as one fish seller points out, she cannot handle the fish if she is wearing gloves. Her protests draw attention to the absurdity of the situation yet similar situations happen everyday where people are killed for not listening to the absurd demands of their invaders. Another such absurd moment happens when the militants forbid the local boys from playing soccer. This results in one of the most beautiful scenes in the film where the kids play soccer without a ball. The kids move around pretending they are passing an invisible ball or taking a shot at goal. This scene is one of the most powerful political protests ever filmed in cinema.

4. Black Girl (1966, Senegal/France, Ousmane Sembene)

5. Moolaade (2004, Senegal co-production, Ousmane Sembene)

In order to oppress the villagers and regain control, the elders decide that radios should be banned because they are influencing the minds of the people and exposing the villagers to dangerous foreign ideas. So an order is issued to collect all the village radios and burn them. This scene echoes the burning of books depicted in Fahrenheit 411.

6. Atlantics (2019, Senegal/France/Belgium, Mati Diop)

A haunting film that adds a new dimension to examine the reason why people undertake risky journeys across treacherous waters and the emotional impact on those who are left behind.

7. Félicité (2017, Senegal co-production, Alain Gomis)

Alain Gomis’ lovely film gives a pulsating tour of the Congolese capital Kinshasa complete with lively sights and electric sounds. We see the extremes in the city from the poor who are trying to make ends meet to the wealthy. The film is powered by an incredible performance by Véro Tshanda Beya who plays the titular character Félicité. Music is a core part of the film and there are scenes which feature live performances by the Kinshasa Symphonic Orchestra which lends a poetic feel to some of the sequences.

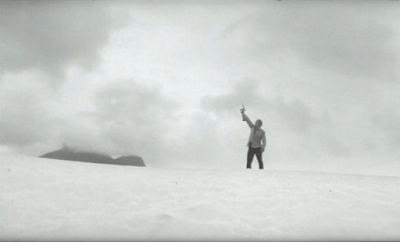

8. This is Not a Burial, it's a Resurrection (2019, Lesotho/South Africa/Italy, Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese)

Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese's film is a cinematic wonder, both in form and content. Visually, the film evokes Pedro Costa’s Vitalina Varela while the topic of a dam and destruction of a village in the name of progress recalls Jia Zhang-ke’s Still Life. However, Lemohang’s film has its own unique tone and rhythm enhanced by the setting of the film in landlocked Lesotho.

9. Tilaï / The Law (1990, Burkina Faso co-production, Idrissa Ouedraogo)

10. Yeelen (1987, Mali co-production, Souleymane Cissé)

Senegal: 5

Mauritania: 2

Burkina Faso: 1

Lesotho: 1

Honourable mentions (alphabetical order):

Abouna (2002, Chad co-production, Mahamat-Saleh Haroun)

Adanggaman (2000, Ivory Coast, Roger Gnoan M’Bala)

Bab’Aziz: The Prince Who Contemplated His Soul (2005, Tunisia co-production, Nacir Kemir)

Cairo Station (1958, Egypt, Youssef Chahine)

Hyenas (1992, Senegal, Djibril Diop Mambéty)

Life on Earth (1998, Mali/Mauritania/France, Abderrahmane Sissako)

Son of Man (2006, South Africa, Mark Dornford-May)

A Summer in La Goulette (1996, Tunisia co-production, Férid Boughedir)

Viva Riva! (2010, The Democratic Republic of Congo co-production, Djo Munga)

Waiting for Happiness (2002, Mauritania/France, Abderrahmane Sissako)

Mauritania: 4

Tunisia: 2

Burkina Faso: 1

Senegal holds on for most titles per country. Mauritania finishes close courtesy of 3 titles by Abderrahmane Sissako.